Non-profit NGO that does not apply for private donations or public subsidies

For an end to slavery-like working conditions for parents and so that children can go to school

For an end to slavery-like working conditions for parents and so that children can go to school

1919 - 2019 - A century ago, the idea of a "global minimum wage" based on a proportion of the median wage or average income of each country and that of a "living wage" were mentioned as soon as the International Labour Organization (ILO) was created. But since then, these drafts have proved to be inapplicable on a global scale.

Today, the "International Convention for a Global Minimum Wage" project could be the only viable global minimum wage proposal since the commencement of the studies in 1919. This comprehensive, pragmatic and structuring economic approach could reduce both inequalities and environmental damage, encourage less but better consumption and may be the best way to achieve the living wage enshrined in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. A reasonable global minimum wage, as we have been advocating since 2013, with 5 to 7 levels of compatibility, initially sectorial, progressive and specific to exported production, could succeed and mark the beginning of a rich economic, ethical and philosophical reflection. Francis Journot

____________________________________

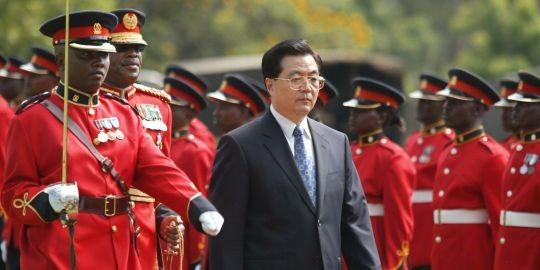

![]() The UN and other institutions whose Malthusian policy aims to control fertility by limiting development and setting new ecological standards that also prevent the industrialization of sub-Saharan Africa, have been mistaken for 60 years. Mostly ideological and dictated by the IPCC, the global investment policy benefits digital and sustainable development funds or actors, often Chinese, at the expense of other activities that would concretely reduce hunger. Only an increase in the standard of living that will encourage the education of children and the emancipation of women will allow, over the years and generations, a reduction in the birth rate. Faced with this failure and the worsening of extreme poverty and even possible famine situations in 45 African countries as a result of the war in Ukraine, world organizations should finally agree to change their policies. They could adhere to the financing of essential structures and infrastructures that we advocate within the framework of the project. The overall cost of development will be very modest in comparison with the inefficiency of past actions which have nevertheless cost more than a trillion euros. Ultimately, the program will reduce poverty on the African continent as well as immigration to Europe, while offering us new opportunities that will create activity and countless jobs in all sectors, in France but also in the EU.

The UN and other institutions whose Malthusian policy aims to control fertility by limiting development and setting new ecological standards that also prevent the industrialization of sub-Saharan Africa, have been mistaken for 60 years. Mostly ideological and dictated by the IPCC, the global investment policy benefits digital and sustainable development funds or actors, often Chinese, at the expense of other activities that would concretely reduce hunger. Only an increase in the standard of living that will encourage the education of children and the emancipation of women will allow, over the years and generations, a reduction in the birth rate. Faced with this failure and the worsening of extreme poverty and even possible famine situations in 45 African countries as a result of the war in Ukraine, world organizations should finally agree to change their policies. They could adhere to the financing of essential structures and infrastructures that we advocate within the framework of the project. The overall cost of development will be very modest in comparison with the inefficiency of past actions which have nevertheless cost more than a trillion euros. Ultimately, the program will reduce poverty on the African continent as well as immigration to Europe, while offering us new opportunities that will create activity and countless jobs in all sectors, in France but also in the EU.

Francis Journot

United States of Sub-Saharan Africa (USSA)

The creation of a homogeneous economic community of sub-Saharan African states facing the same demographic and malnutrition problems could prove relevant. More economically operational and executive than political and administrative, this community must aim to free itself from ideologies in order to better reconcile the imperatives of environmental preservation and the industrialization that is essential to modernize the region and reduce extreme poverty. Published the Wednesday, March 26, 2025

United States of Sub-Saharan Africa (USSA) & Program for the Industrialization of Sub-Saharan Africa.

![]()

Francis Journot : "If Europe doesn't help

sub-Saharan Africa to industrialize,

immigration will explode"

Le Figaro/Tribune published october 20, 2021. The population of sub-Saharan Africa is expected to double by 2050. It is therefore urgent that this one develops, with the help of international companies, its own industry, for consumer goods, which will create jobs and also respect its environment. However, since the climate issue has become an absolute priority, we have seen a shift in funding towards green or digital projects, even when they do not create jobs. But this policy, which would prevent industrialization and keep Africa in poverty, would also cause an explosion of migratory flows to France and other EU countries.

he issue of industrialization of Africa to avoid chaos is more crucial than climate change

If Africa fails to industrialize and modernize, we will see an increase in situations of extreme poverty, malnutrition and subsequently chaos across the continent. Several hundred million Africans among a population which should number 2.5 billion inhabitants in 2050, will then wish to come to France and Europe to flee hunger and death.

The democracies which protect Europeans from war and disorder will not be able to survive this upheaval. The collapse of Western civilization in a more or less distant future is often mentioned. It could now happen in less than 3 decades. Whether we think that the origin of climate change is mainly anthropogenic or not, the subject of the economic development of sub-Saharan Africa to avoid chaos, appears more urgent than that of climate.

International institutions are aware of the unprecedented crisis that is brewing

In sub-Saharan Africa, the region with the highest demographics, the number of people suffering from malnutrition was estimated at 236 million in 2017 among 431 million living in extreme poverty. According to international institutions, these figures could double or triple in the years to come. 30 million young workers enter the African labor market each year, but only 10-15% of them find employment. Out of idleness, some join Islamist sects.

The International Labor Organization (ILO) estimates that informal employment rates among young people aged 15 to 24 reached 94.9% in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2018 and up to 97.9% (Senegal) in French-speaking countries in Africa. from West. The UN is aware of the looming humanitarian crisis because, according to it “If the current trend continues, by 2030 Africa will be home to more than half of the chronically hungry people in the world».

Green finance policy could hinder Africa's industrial development

The approach of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the UN for 2030, foremost among which are extreme poverty and hunger, is holistic. But the 17 desired indivisible and transversal objectives are often opposed to each other. The IPCC, which brandishes the threat of 250,000 additional deaths per year due to climate change, calls for carbon neutrality which would however go against the progress of work and industry in emerging or developing countries.

This policy will condemn hundreds of millions of people to remain in extreme poverty at a time when nearly 900 million are undernourished in the world and one million of them die each month from this scourge. So reserve funding for projects only because they meet green or digital criteria when we know that these will create little or no jobs and will most often fail for lack of efficient infrastructure or ecosystems, would be unwise. Moreover, everyone knows that poverty in Africa constitutes a fertile ground on which Islamic terrorism thrives. Also, this green finance policy, also claimed by the French Development Agency (AFD), could have the effects of maintaining sub-Saharan Africa in underdevelopment and weakening France as well as other countries.

Degradation of the industry since the end of colonization

Judging by the current state of sub-Saharan industry, one can only wonder about the method of international institutions and the lack of willingness of African or Western decision-makers to industrialize. The world community has been wrong for 6 decades but has been deluding itself by funding NGOs and distributing alms. Africa’s industry and economic situation have been deteriorating for 60 years.

For example, in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), from 9,600 industrial companies inherited from Belgian colonization, the number rose to 507 recently identified. However, the abundant labor force and wages lower than those of Western countries, could constitute a competitive advantage which could attract industrial investments. Building a manufacturing industry capable of producing its own consumer goods would be the best way to create jobs and eradicate extreme poverty and hunger. The competitive advantage will make it possible to export.

We must break with a condescending and humanitarianist discourse held by NGOs and institutions, according to which Africans can only find economic salvation by migrating to a West which would be responsible for all their ills.

Sub-Saharan Africa must be able to produce consumer goods

The new, ambitious, trained and graduated African generations are ready to take up this challenge of industry and modernization, but only a comprehensive industrialization plan for sub-Saharan Africa would allow it. The goods bought by Africans are today mainly imported from China but the proposal of “Transfer from China to Africa, part of industrial production», is well received by these.

After more or less agreed transfers of know-how and technologies to Chinese companies now in competition and a growing mistrust, a “Europe Africa production regionalization plan Could convince many large companies around the world to change their global value chains (GVCs). Given the high cost of labor in most Western countries as well as the weight of taxes and standards, labor-intensive industries will only very rarely return. However, cost equalization and pooling mechanisms would allow European companies to regain competitiveness. The huge future African market would offer us new perspectives and also promote growth in France and Europe. Sharing of know-how and new exchanges would benefit the States and populations of the two continents.

The EU's dogmatic green taxonomy already deadly for the European economy

In some industrial companies, the gas and electricity bill has almost doubled in a few years. Taxes and standards weaken industries for the benefit of China. Industrial sectors are being rolled back and will put millions of European workers out of work. The EU shuns nuclear energy which emits little CO₂ but promotes energy transition products made in China including batteries and electric cars with devastating ecological footprints or wind turbines and voltaic panels also partly financed by French and European subsidies.

The involvement of women in industry would reduce the demographic balance and poverty

In addition, when several tens of millions of women from sub-Saharan Africa, will run artisanal or larger businesses, will occupy industrial positions and three or four times more service jobs, indirect and induced, the birth rate and the poverty rate will fall naturally.

If we add to this, that an increase in the standard of living will encourage the education of children and the emancipation of women, the family model will evolve. Thus the African demographic balance will decrease by several hundred million inhabitants and defeat current forecasts.

Sacrificing a part of humanity in the name of the climate precautionary principle would be madness

Let us not forget, before preventing the development of sub-Saharan Africa or destroying more economic balances in Europe, that climatology is a science of interactions, of which by definition, the multiplicity of factors, the many disciplines involved and the lack of predictability, should prompt us to be more humble and cautious. It is doubtful whether the ecological paradigm which risks undermining many economies around the world and thus condemning hundreds of millions of poor people to hunger and death, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, will win unanimous support among the individuals. more concerned.

European populations could also, when the migratory tsunamis have got the better of social protection systems, their culture and their civilization, regret having given in to dogmatism. So it seems risky to advocate, in the name of a principle of climate precaution, an ideological policy that will surely sacrifice a large part of humanity. Perhaps tomorrow we will have to face the gaze of new generations who will judge our mistakes. Let us hope that the international institutions take the measure of their responsibility and the possible consequences of their dangerous policy.

Consultant and entrepreneur, Francis Journot is the founder of the United States of Sub-Saharan Africa project and the Program for the Industrialization of Sub-Saharan Africa or Africa Atlantic Axis. He is also the initiator of the International Convention for a Global Minimum Wage and runs the website Collectivité Nationale

We must transfer from China to Africa,

We must transfer from China to Africa,

a part of industrial production

Financial Afrik /Tribune by Francis Journot, published on June 01, 2021. This global paradigm shift would enable the modernization of Africa and would offer some countries the possibility of escaping the Chinese trap of African debt in order to preserve their sovereignty. The installation of infrastructure and industrial tools of often Western companies as well as the creation of a large network of local companies would generate tens of millions of jobs on African soil that would be more remunerative than those in the informal sector. This transformation, which would nevertheless be respectful of the environment, would promote new exchanges between African states and their partners, often French, European, American and sometimes Asian. It would increase the growth of each of them.

Financial Afrik /Tribune by Francis Journot, published on June 01, 2021. This global paradigm shift would enable the modernization of Africa and would offer some countries the possibility of escaping the Chinese trap of African debt in order to preserve their sovereignty. The installation of infrastructure and industrial tools of often Western companies as well as the creation of a large network of local companies would generate tens of millions of jobs on African soil that would be more remunerative than those in the informal sector. This transformation, which would nevertheless be respectful of the environment, would promote new exchanges between African states and their partners, often French, European, American and sometimes Asian. It would increase the growth of each of them.

When ideology prevents the development of Africa and maintains poverty

At international summits, at a time when extreme poverty and famine are wreaking more havoc than ever, Westerners and well-fed Africans frequently explain to a population of 250 million people suffering from malnutrition in an Africa that is virtually devoid of industry and has low CO2 emissions, that the priorities must be digital transformation and a green transition of uncertain contours. Whether this is technocratic thinking, cynicism, dogmatism or ignorance of the African economy, everyone will judge. But the prioritization of insufficient or illusory proposals that will not produce significant effects quickly in economic matters, is likely to delay the development of the continent and worsen poverty.

A model that could meet the aspirations of African youth

At the end of 2020, in an article published on La Tribune Afrique entitled "Sub-Saharan Africa : capitalism could succeed where development aid has failed for 60 years", we questioned the effectiveness of public aid that has exceeded $1,000 billion but has not succeeded in reducing informal employment, which still concerns 85 to 89% of the active sub-Saharan population. Industrial enterprises would provide better-paying jobs. The reasonable increase in production wages that we advocate in our studies on the "International Convention for a Global Minimum Wage" project would also contribute to a rise in the standard of living of the population and accelerate Africa's development. This could respond to the wish of many Africans who would like to make a better living from their work and break away from assistance that is certainly benevolent and often indispensable but that reflects a negative image that they want to change.

Structured plan for industrial regionalization in sub-Saharan Africa

As we have already written in french newspaper Le Figaro, "Reducing our dependence on China is possible !". But only a "Europ-Africa production regionalization plan", realistic and structuring but also taking into account the new geopolitical and geo-economic parameters, could succeed. A financial involvement, even moderate, of each of the countries that would like to strengthen their economic presence to increase their trade with Africa within the framework of the program, would be essential. Companies from these foreign signatory states could benefit from support to facilitate their establishment (recruitment and training, legal, fiscal and administrative assistance, financing, studies, etc.) which would contribute to the attractiveness of sub-Saharan Africa. We will be able to build global industrial schemes within which they can project themselves and which will convince them to move part of their production. It will be necessary to look for sectoral complementarity in order to create efficient and coherent ecosystems. This proximity will also help reduce the transportation of materials or parts within global value chains (GVCs).

A concrete and easily financed program

The cost of building industrial bases, including road, rail, airport or port access, energy supply, telecommunications networks, roadworks, waste management, but also security devices, housing, schools, medical centers and essential shops, would be eligible for funding by major international institutions and donor countries as part of Africa's development. The amount spent for each industrial site that would be built every 2 or 3 years would be around 3/5 billion euros. In contrast to policies or economic proposals, international or local, often hollow and without a future, but which have sclerotised the development of sub-Saharan Africa for 60 years, the "Africa Atlantic Axis" program could on the contrary, be implemented in the medium term if the populations of the African countries most concerned so wish. The international financial institutions could only join this project of progress for Africa. Indeed, this process of industrial integration would increase the budgetary resources of States. It would allow the securing of territories, would raise the purchasing power of populations and would offer enormous development perspectives for a continent whose economic construction would require the energy of all its youth.

Consultant and entrepreneur, Francis Journot is the founder of the United States of Sub-Saharan Africa project and the Program for the Industrialization of Sub-Saharan Africa or Africa Atlantic Axis. He is also the initiator of the International Convention for a Global Minimum Wage and runs the website Collectivité Nationale

![]() Reducing our dependency to China,

Reducing our dependency to China,

it is possible!

Le Figaro/Tribune by Francis Journot, published on June 08, 2020 - By relying more on its regional market, Europe is able to significantly reduce its dependence on Chinese industry, says Francis Journot.

Le Figaro/Tribune by Francis Journot, published on June 08, 2020 - By relying more on its regional market, Europe is able to significantly reduce its dependence on Chinese industry, says Francis Journot.

Few risks of shortages or sharp price increases

In the light of a crisis that reminds us of the fragility of our existence and a confinement that has made us aware that we can deprive ourselves of over-consumption for two months, it seems certain that we would be able to survive a period of transfer of Chinese industry. Some products that are not always indispensable could become scarce, but let's be reassured, most imports would continue to pour in because companies and their shareholders do not appreciate consumers deserting the stores. Every search for new subcontractors would result in a multitude of competitive service offers around the world, and hundreds of thousands of engineers would want to participate in the development of production processes. As for the vital area of food, European countries have little dependence on the rest of the world. So it is doubtful that we should fear real shortages or a significant increase in the prices of our consumer goods, but we could, on the other hand, consume less but better and rejoice in relocations that would, over the months and years, lift millions of Europeans out of unemployment and poverty.

A new European paradigm based on a broader regionalization of production and trade that includes more Africa.

Rising wages and manufacturing costs in emerging or developing countries accompanied by a drop in direct investments, technology theft and counterfeiting, the environmental cost of transport and consumer demand for more local products, we have been witnessing for several years now to phenomena which indicate or provoke a decline in globalization. Although not yet evident, the Covid-19 crisis and the rise in unemployment could accentuate a trend towards regionalization of trade. Europe could initiate a new European paradigm of regionalization of value or production chains within the framework of the EU or a less political economic community if it disappears. But relocating activities to France would not be easy. One would have to exempt oneself from sclerosing ideologies with their elitist postulate of selecting only the so-called strategic sectors. This has justified the delocalization of other activities and has proved to be erroneous. Manufacturing jobs generated many indirect and induced jobs whose contributions and taxes better financed public spending, moderated the cost of labor, allowed maintaining a better level of technical training that benefited all sectors, including the most strategic, and thus participated in a virtuous economic circle.

The new conception of trade proposed here obviously differs from the unrealistic recommendations of autarky and the end of globalization made by the former Minister of Economy Arnaud Montebourg. For beyond the slogan "made in France" and the theme of reindustrialization regularly exploited for political purposes by personalities in search of publicity and voters but often from government parties whose economic policies have favored deindustrialization, there remains the reality of the cost of labor but also the pitfalls of a highly politicized dogmatic trade unionism and the innumerable norms that discourage industrialists. The mechanisms of mutualization and equalization would be likely to promote the creation of ecosystems and jobs, but a relaxation of European or national treaties and regulations that make the management of French companies more cumbersome would also be desirable.

There are many obstacles to a massive return of jobs in France and sometimes even in Europe.

With a rich market of 500 million consumers, the growth potential in Europe is enormous. The lower-cost European countries would experience full employment, but in other countries we could come up against a mismatch in the supply of industrial jobs for job seekers who are not attracted by these opportunities. In France, skilled labor has virtually disappeared in many industrial sectors, but also in many European countries. The cost of training for each job is often around 20/50 K€, mostly borne by the company, but this does not guarantee that candidates will be able to carry out work for a long time that is often considered to be arduous. Today, small and medium-sized companies in the industry are unable to train more than one or two jobseekers per year. It is doubtful whether European industry will be able to recruit all the necessary staff. Moreover, the level of exports could erode after a few years. China will further reduce imports to cope with unemployment that could weaken power and the USA is showing a strong willingness to relocate since 2017. Western companies established on its soil have brought it the technologies that will enable it to meet all the needs of its consumers. Also, new non-European prospects would be harder to find and each European country would try to pull its own cover in order to gain market share within Europe, as is already often the case today. The luxury goods sector would continue to do well, but there are fears that the number of orders would decline in leading-edge sectors facing growing competition, including China. One could hope for the emergence of European leaders in new fields, but this would take time. Nevertheless, France and the countries of Europe would welcome the reduction in imports and a return to prosperity in many sectors. But after an upturn in activity and a drop in unemployment, the economy could turn in circles and return to low growth and employment rates.

With sluggish growth and unemployment in the EU, poverty and galloping demographics on the neighbouring continent, we are facing many challenges

So we are confronted with these challenges but also many others for which we will have to try to find solutions sooner or later. Among these, the phenomenon of the galloping demography of a continent less than 150 kilometers from the first European coasts, which could have two and a half billion inhabitants in 2050. An important part of them would try to flee misery and hunger by migrating to a weakened Europe, hardly able to offer better living conditions. However, the foundations of our civilization, political and economic, cultural and religious, would not survive. The social and security chaos that could set in could precede or surpass the climate collapse promised by environmentalists who are committed to an ideology of degrowth to which our African friends who are struggling to feed themselves may not fully adhere. So perhaps, in order to solve our growth problems in the years to come but also contribute to poverty reduction in a nearby continent that is experiencing exponential demography, we could reflect on a model that broadens our cooperation with it.

China perverts rather than enriches the African continent

Today, China intends to get its hands on this enormous reservoir of raw materials. But it perverts more than it enriches this continent by flooding it with low-cost products from Asia and thus makes craftsmen or small businesses that used to make local products more precarious. The factories created belonged to companies dependent on Beijing, whose Chinese foremen ran some of the worst paid workers in the world. These low wage levels thus allow China to flood Western countries with low-end products without benefiting the African people in terms of social progress. But this rampant colonization, which is increasingly badly experienced, arouses bitterness.

Eventually, more industrial autonomy

It is essential for Africa to equip itself with the means to ensure the subsistence of its population while taking care to preserve its fauna and flora. Many engineers wishing to see Africa and the Maghreb grow would enthusiastically welcome this transcontinental project of creating joint ventures within sectoral clusters. These new production tools, which would first of all be integrated into European supply chains, would promote the economic development of the countries and would facilitate their access to greater industrial autonomy. The cost of setting up the plants would be covered by the brands or brands to which the products are destined. The companies, organized in collectives, could thus benefit from a mutualization of costs but also from a modularization of production in certain sectors. These activities would provide new local opportunities for young generations currently tempted by immigration to Europe. Funds considered inefficient among those currently allocated to the development and support of countries could be redirected towards the construction of the necessary infrastructures, which would thus benefit everyone, since it seems more relevant to invest upstream by creating jobs and generating an increase in local living standards rather than continually acting downstream.

Indeed, the assistance, although benevolent and often indispensable, nevertheless conveys an image that this continent wishes to erase in order to change the perception of the world and move forward. Profitable and growing groupings of companies would certainly attract global capital that would then abound with new projects and accompany the expansion of the model across the continent to perhaps make it a new Eldorado.

One can think that a rise in the standard of living in Africa would encourage the education of children, the emancipation of women and eventually a reduction in the birth rate.

This prolific partnership for Africa would also be prolific for Europeh witch needs new perspectives. The implementation of the project would require the assistance of many companies with expertise in industrial engineering, energy, construction, digital, training in the many sectors, human resources etc. The number of positions straddling the two continents would be considerable. France has retained privileged links with most countries and would have an important card to play. Subsequently, the African continent could eventually constitute for Europe a new growth relay that would fill a slump in Chinese demand, especially since it has as many inhabitants as China. Their purchasing power is not comparable, but let us remember that at the dawn of this millennium, China's GDP per capita was similar to that of most African countries that it has now undertaken to colonize. It is difficult to grasp the full dimension of such a regionalization project as the implications and possibilities are multiple in terms of employment and wealth creation. Demographic forecasts predict a doubling of the African population within thirty years, but one can think that an increase in the standard of living would encourage the education of children, the emancipation of women and, in the long run, a reduction in the birth rate. A reasonable and evolutionary increase in monthly production wages, which today usually vary between 35 and 200 euros, could accelerate this sociological change.

It would therefore be possible to build an alternative to Chinese dependence. Why settle for maintaining our industries in China, favouring a hegemony that will hinder our freedoms and will certainly expose us sooner or later to the risk of a world war, when a regionalization of trade would give us the opportunity to consume less but better without, given the international competition, making prices soar and would, moreover, offer us economic dynamism and the creation of millions of jobs at a time when unemployment is ravaging Europe while allowing the neighbouring continent to achieve greater social progress.

Consultant and entrepreneur, Francis Journot is the founder of the United States of Sub-Saharan Africa project and the Program for the Industrialization of Sub-Saharan Africa or Africa Atlantic Axis. He is also the initiator of the International Convention for a Global Minimum Wage and runs the website Collectivité Nationale

A global minimum wage to reduce inequality

Marianne/Tribune by Francis JOURNOT, published march 16, 2020 - In order to reduce inequalities, the "Patriotic Millionaires" collective proposes a taxation of the richest, which however does not seem to be unanimously supported. Could a reasonable global minimum wage project, which takes into account economic realities, be more convincing?

Marianne/Tribune by Francis JOURNOT, published march 16, 2020 - In order to reduce inequalities, the "Patriotic Millionaires" collective proposes a taxation of the richest, which however does not seem to be unanimously supported. Could a reasonable global minimum wage project, which takes into account economic realities, be more convincing?

In a letter entitled Millionnaires against pitchforks signed in Davos by 121 personalities, the "Patriotic Millionaires" collective urges its millionaire and billionaire friends around the world to demand higher and fairer taxes in order to reduce "extreme and destabilizing inequalities". The initiative is generous, but it is doubtful whether it alone will significantly reduce poverty and the negative effects of low-cost production on the environment. Moreover, calls for accountability, however sincere, are rarely heeded. We should therefore try another approach to reach this goal, because the recommended philanthropy is obviously commendable, but the working poor, for their part, want a little more equity in the remuneration of their labor.

In a letter entitled Millionnaires against pitchforks signed in Davos by 121 personalities, the "Patriotic Millionaires" collective urges its millionaire and billionaire friends around the world to demand higher and fairer taxes in order to reduce "extreme and destabilizing inequalities". The initiative is generous, but it is doubtful whether it alone will significantly reduce poverty and the negative effects of low-cost production on the environment. Moreover, calls for accountability, however sincere, are rarely heeded. We should therefore try another approach to reach this goal, because the recommended philanthropy is obviously commendable, but the working poor, for their part, want a little more equity in the remuneration of their labor.

The International Convention for a Global Minimum Wage project, which was born in 2013, could provide solutions. Reasonable and progressive, it advocates pragmatism and recommends reintroducing balances upstream of economic mechanisms. Today, this could be the only way to both reduce inequalities in the world and the ravages of over-consumption on the environment. This global minimum wage, which would include several levels to take into account economic disparities, could be implemented in most countries in less than 7 or 8 years.

First Attempts

In the aftermath of the First World War, the world minimum wage became a priority and was one of the first projects of the ILO created in 1919 under the aegis of the Treaty of Versailles. Researchers were quick to identify the obvious first steps towards a world minimum wage based on a proportion of the median wage or income of each country (50 or 60% often cited) and the more or less similar Living Wage. But it is possible that ILO economists became aware of certain risks before the 1928 Convention. Indeed, taking into account a median wage, whether high or low, in the calculation of a local minimum wage does not guarantee that a State will then be able to cope in certain cases with an increase in the remuneration of its civil servants or that the rate of inflation that could be caused by a generalization of the minimum wage will be contained and will hardly aggravate situations of poverty. The danger of generating unrest and the bankruptcy of certain States has certainly tempered the desire for social progress and prompted caution. The Convention concerning the Creation of Minimum Wage-Fixing Machinery therefore left the signatory States free to decide: "Each Member which ratifies this Convention shall be free to determine the methods for determining minimum wages and the detailed rules for their application". 99 countries have ratified a convention that has not prevented inequalities from growing. The global minimum wage never saw the light of day and has been dormant ever since.

The danger of generating unrest and the bankruptcy of certain States has certainly tempered the desire for social progress and prompted caution. The Convention concerning the Creation of Minimum Wage-Fixing Machinery therefore left the signatory States free to decide: "Each Member which ratifies this Convention shall be free to determine the methods for determining minimum wages and the detailed rules for their application". 99 countries have ratified a convention that has not prevented inequalities from growing. The global minimum wage never saw the light of day and has been dormant ever since.

Failure of the European minimum wage

The idea of a European minimum wage has not been specifically theorised for the European Union by some eminent researcher or by a group of elected representatives, but has simply been inspired by the work of the ILO.  This political project emerged in the 1990s in order to enhance the social Europe dear to its founding fathers but has since come up against the structural disparities of the 27 countries of the European Union. Nevertheless, it is understandable that the governments of the lower-cost European countries, like their more distant competitors, are reluctant to raise wages and thus expose themselves to a reduction in their competitive advantage. It is therefore essential, in the context of globalisation, to include this issue in a broader process of global minimum wages.

This political project emerged in the 1990s in order to enhance the social Europe dear to its founding fathers but has since come up against the structural disparities of the 27 countries of the European Union. Nevertheless, it is understandable that the governments of the lower-cost European countries, like their more distant competitors, are reluctant to raise wages and thus expose themselves to a reduction in their competitive advantage. It is therefore essential, in the context of globalisation, to include this issue in a broader process of global minimum wages.

A structured concept for a global minimum wage based on concrete financial resources

In order to convince the countries concerned, a clear, realistic and economically structuring project should be proposed. If we consider that the question of financing the world minimum wage remains one of the main stumbling blocks for States, we must resolve to intervene only on wages that are likely to benefit from resources that allow it, first and foremost those of workers producing items for export. For example, a differentiated, gradual and programmed increase over several years in monthly wages, currently $25 in Ethiopia, $90 in Bangladesh, $170 in Vietnam or $300 in Bulgaria, would only impact the price of clothes sold most often to European or American consumers by a few tens of cents or even a few dollars on more expensive items. A timetable, based on comprehensive analyses, would prepare the conditions that would then enable international agreements to be signed. The EU and international institutions could share data or collaborate more widely on the basis of a common methodology. Partnerships with research departments of prestigious universities could also help to enrich this content. Positioning the cursor on minimum wage targets which might appear unambitious but which few countries could therefore refuse, would certainly not be likely to instantly change the living conditions of the 300 million working poor who live on less than $1.8 euros a day or of those who receive little more. On the other hand, this increase in remuneration, which would, however, initially concern only a part of the sectors of activity and populations, would secure this change and, above all, would make it possible to finally get a project for a world minimum wage on the rails, which should have 5 to 7 levels of compatibility.

A non-ideological project

Inequalities and "living wage" are part of the struggles or are favorite themes of NGOs which receive a financial windfall of several tens of billions of euros every year. But local actions can only partially solve these problems because the globalized economy requires us to think on a different scale first. The subjects of the global minimum wage and inequalities are, unfortunately, most often exploited for political, ideological or pecuniary ends. For many NGOs and medias (The Guardian, Jacobin, The Nation, the New Republic, Inequality, etc.), they constitute contents that tend to testify to their humanity or their commitment. But the extreme demands and the counter-productive publication of unrealistic ideological proposals, whose manicheism sometimes has nothing to envy to communism, provide arguments to the detractors of this cause which is thus discredited and immobilized. These opinion leaders, whose role-playing or lack of foresight can be regretted, ultimately do a disservice to those they claim to defend.

The subjects of the global minimum wage and inequalities are, unfortunately, most often exploited for political, ideological or pecuniary ends. For many NGOs and medias (The Guardian, Jacobin, The Nation, the New Republic, Inequality, etc.), they constitute contents that tend to testify to their humanity or their commitment. But the extreme demands and the counter-productive publication of unrealistic ideological proposals, whose manicheism sometimes has nothing to envy to communism, provide arguments to the detractors of this cause which is thus discredited and immobilized. These opinion leaders, whose role-playing or lack of foresight can be regretted, ultimately do a disservice to those they claim to defend.

After 7 or 10 years if we count the previous related work, the International Convention for a Global Minimum Wager project, noticed as early as 2013 by American academics, now benefits from a worldwide network of nearly 7,000 experts, most of whom are likely to be in agreement of the project or at least in favor of a reflection on the proposals put forward.  Most of them hold a PhD in economics or finance and several hundred of them wish to participate in the studies. Among them are many researchers and professors who teach in American Ivy League universities (Harvard, Yale, Columbia, Cornell...) or at Stanford, Berkeley, MIT and other prestigious schools around the world, but also nearly two thousand economists working in international institutions such as the UN, the WTO, the World Bank, the IMF, the World Economic Forum or the ILO as well as managers and financiers of large companies, banks or investment funds who know as we all do that increasing inequality can be dangerous.

Most of them hold a PhD in economics or finance and several hundred of them wish to participate in the studies. Among them are many researchers and professors who teach in American Ivy League universities (Harvard, Yale, Columbia, Cornell...) or at Stanford, Berkeley, MIT and other prestigious schools around the world, but also nearly two thousand economists working in international institutions such as the UN, the WTO, the World Bank, the IMF, the World Economic Forum or the ILO as well as managers and financiers of large companies, banks or investment funds who know as we all do that increasing inequality can be dangerous.

A global minimum wage offer that is difficult to refuse

So what leader of low-cost countries, inside or outside Europe, could publicly oppose a convention offering the opportunity for his fellow citizens working for export to the major, mainly Western, consumer markets to gradually benefit from better pay and living conditions that would mechanically, over the years, extend to all workers and then benefit the entire population without significantly affecting competitiveness if the increases are then coordinated on a global scale. Given the sectoral nature of these increases, they would not cause inflation to soar. Nor would the pact force governments to increase public spending, since the project is not based on a utopian and sudden general increase in wages. Environmental resources and natural habitat would be less strained. A generation tempted by immigration would discover new opportunities and sometimes choose to participate in local expansion. Supernatality exacerbates food insecurity, which today affects nearly one billion people worldwide. Thus, measures would often promote the education of children, the emancipation of women and, ultimately, a reduction in the birth rate and poverty. As the signatories of the Millionnaires against pitchforks letter warn, we must act before it is too late.

Consultant and entrepreneur, Francis Journot is the founder of the United States of Sub-Saharan Africa project and the Program for the Industrialization of Sub-Saharan Africa or Africa Atlantic Axis. He is also the initiator of the International Convention for a Global Minimum Wage and runs the website Collectivité Nationale

![]() It's time to stop telling the tale

It's time to stop telling the tale

of the European minimum wage

Nathalie Loiseau, head of the list of the french presidential party LREM during the European elections

Nathalie Loiseau, head of the list of the french presidential party LREM during the European elections

Le Figaro/Tribune by Francis Journot, published mai 14, 2019 - Francis Journot, initiator of the "International Convention for a Global Minimum Wage" project, explains why it is illusory to believe in the "European minimum wage" by arguing that the project is incompatible with the structural disparities of the 28 countries of the European Union. He advocates for a global minimum wage in other ways.

The theory of a European or global minimum wage based on a proportion of each country's median wage has always proved unconvincing and few economists still support it today. The International Labour Organization (ILO) has renounced the introduction of this model for several decades. The European Commission is now avoiding this subject, which annoys Member States and prefers to refer to a more general notion of "European economic and social convergence" or the equally sibylline objective of a "European foundation of social rights".

But French President Emmanuel Macron, certainly short of progressive ideas, woke up this old sea snake. However, the project is incompatible with the structural disparities of the 28 countries of the European Union and would be hazardous. Candidates for election to the European parliament are now engaged in a real competition and the recommendations vary almost from single to double: Nathalie Loiseau, head of the list of the presidential party LREM, wants a European minimum wage corresponding to 50% of the median salary of each EU country and a social policy expert teaching at the ENA and affiliated to LREM, recommends, in an article published in newspaper Liberation, 40 to 50%. The Generation S lists of Benoit Hamon, PC led by Ian Brossat and EELV of Yannick Jadot opt for 60%. Raphaël Glucksmann, head of the list Public Policy and PS wants 65% while Manon Aubry of LFI outbids with 75%.

The candidates did not seem to consider it useful to carry out simulations or perhaps they preferred demagogic simplification to the rigour of the figures. Indeed, instead of the desired increase in the standard of living and the targeted convergence, we could see, on the contrary, depending on the rate recommended, a decrease in half of the countries in minimum wages, some of which are already among the lowest in Europe or often an increase in the differential between minimum wages. Moreover, if we consider that public expenditure in the EU countries is on average close to 50% of GDP, a significant proportion of which is represented, depending on the structure and outsourcing of services, by the cost of public or private jobs, it appears that this measure could generate an increase in the public deficit in some countries and, moreover, would sometimes cause them to exceed the authorised limit of a 3% public deficit. The inflation risk that can be encountered when the minimum wage is raised is also not anticipated. However, there is no cause for concern as this project would probably never achieve the required unanimity within the EU and will be buried until the next European election, but the fanciful treatment of this major economic issue may be appalling.

This idea of a European minimum wage, which appeared in the 1990s, brandished to promote the social Europe dear to its founding fathers, was not specifically theorized for the European Union by any distinguished researcher or by a group of elected officials, but simply borrowed from the International Labour Organisation. But at a time when the EU had only 12 to 15 Member States with broadly similar living standards and a reasonable rate of new accessions, the option was conceivable (France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands when the EEC was created in 1958, Denmark, Ireland and the United Kingdom in 1973, Greece in 1981, Spain and Portugal in 1986, East Germany in 1990, Austria, Finland and Sweden in 1995). However, the number of Member States doubled over the next two decades and the homogenisation of the European Union by this means now seems utopian. However, it is understandable that governments in lower-cost European countries, like their more distant competitors, are reluctant to raise wages and thus expose themselves to a reduction in their competitive advantage. This should be taken into account when developing a draft minimum wage.

It is therefore essential, in the context of globalisation, to examine the subject of the minimum wage in Europe from a broader perspective. After 6 years of work and nearly a decade, if we include the related subjects that initiated this reflection, the "International Convention for a Global Minimum Wage" project, which could reintroduce balances upstream of international economic mechanisms, now benefits from a network of several thousand economists throughout the world, most of them experienced and holding a doctorate in economics. The concept integrates economic realities and is based on fundamental parameters (financial flows, budgetary capacity of States, nature of trade, industrial activity, etc.) to propose a consensual and pragmatic timetable. In this field, it could constitute today the only viable proposal likely to reduce inequalities but also the damage of consumerism on the environment at a time when the main current response seems to be the multiplication of "climate" taxes that are as unfair as they are inefficient but above all demanded by parties and NGOs for a political and ideological ecology. But the instrumentalization of the themes of minimum wages or ecology is counterproductive and is to the detriment of more objective economic approaches and rational solutions.

Consultant and entrepreneur, Francis Journot is the founder of the United States of Sub-Saharan Africa project and the Program for the Industrialization of Sub-Saharan Africa or Africa Atlantic Axis. He is also the initiator of the International Convention for a Global Minimum Wage and runs the website Collectivité Nationale

_______________________________________________________

![]() European and global minimum wage:

European and global minimum wage:

Open letter to the President of the

European Commission Jean Claude Juncker

Le Figaro/Tribune by Francis Journot, published april 11, 2019 - Francis Journot, initiator of the "International Convention for a Global Minimum Wage" project, publishes an open letter in favour of a "global minimum wage". He believes that it could reduce the damage that consumerism does to the environment.

Le Figaro/Tribune by Francis Journot, published april 11, 2019 - Francis Journot, initiator of the "International Convention for a Global Minimum Wage" project, publishes an open letter in favour of a "global minimum wage". He believes that it could reduce the damage that consumerism does to the environment.

The European Commission's Directorate General for Employment and Social Affairs, which is in charge of replying to my recent letter, recalls the framework of the "European Foundation of Social Rights" proclaimed on 17 November 2017 in Gothenburg and the principle relating to wages, which mainly provides that "appropriate minimum wages must be guaranteed, at a level allowing the needs of workers and their families to be satisfied".... However, the Commission is well aware of the impossibility of establishing a European minimum wage within the current legal framework defined by the Treaties and regrets: "the competence to set wages and minimum wages lies mainly with the Member States" and "any proposal for a European framework for minimum wages should be approved by the Member States". So, if we add to this, the opposition of the likely future German Chancellor Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer (AKK) to the model based on a percentage of the median salary, recently proposed by the French President Emmanuel Macron or by the EU previously, to which many Member States are also opposed, we can then consider that you currently have no effective solution in this matter and it seems urgent to change the method.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) has been trying to establish a global minimum wage since its foundation in 1919 and the EU has been trying in Europe for 20 years. The UN denounces consumerism and the destruction of the environment. The World Bank, the IMF, the WTO and the World Economic Forum have expressed concern about rising inequality. It is therefore necessary to combine actions. However, international institutions and the EU are trapped in excessively cumbersome protocols and room for manoeuvre is limited. Examples include the ILO's tripartite structure or the principle of unanimity among EU members. So how do we implement it?

The "International Convention for a Global Minimum Wage" project

In a globalised world, competition between low-cost countries is obviously global and we must therefore understand these issues as a whole. Wages in the EU cannot be increased unilaterally without risking affecting the economies of some of its member countries. But at a time when everyone regrets the damage that consumerism has done to the environment and the rise in inequality, States around the world could, as part of a global consensus, be inclined to take a step towards a more virtuous model together. To do this, we would have to propose a realistic timetable based on personalised studies.

The positioning of the cursor on minimum wage targets that may appear unambitious but that few countries could therefore refuse, would certainly not be likely to instantly change the living conditions of the 300 million working poor who live with less than 1.7 euro ($2) per day (source ILO) or those who receive barely more. On the other hand, this increase in remuneration, which would, however, initially concern only a part of the sectors of activity and populations, would secure this change and would, above all, make it possible to finally set in motion a project for a global minimum wage that has been dormant for nearly a century. Without it, the European minimum wages, particularly in the consumer goods manufacturing industry, would prove complicated or even impossible.

It would therefore be appropriate to create a more agile and private-law dedicated structure, capable of pooling will and skills, but duly mandated by the EU and international institutions to prepare the conditions that will then allow the signature of international agreements.

A strategy based on both economic expertise and a relevant communication could promote the establishment of a global minimum wage with 5 to 7 levels of compatibility. In continuity with the work already carried out and the leads identified since 2013 in the framework of the "International Convention for a Global Minimum Wage" project, more than 200 researchers could carry out analyses of the economic parameters of each of the countries concerned. Among these, many recognized experts would work, already experienced in these issues and often belonging to our large global network which now includes nearly 4,000 economists (most of whom hold a PhD in economics). Their counterparts in the EU and international partner institutions could share data or collaborate more broadly on the basis of a common methodology. The roles of the ILO and the WTO (World Trade Organization) could prove decisive.

Research departments at prestigious universities could enrich this content. The full reports would sometimes include several hundred pages of analysis per country and projections whose exclusively technical and non-partisan treatment and interpretation would guarantee their objectivity. These would then be used to draw up the fair schedules proposed to States. They should make it possible to limit as far as possible the risks of economic dysfunction and to contain inflation phenomena.

The other essential aspect of our mission would be to explain this little-known and complex subject to as many people as possible. To be successful, the minimum wage must be perceived by all countries as an opportunity for social and economic progress, sometimes even as protection. For example, in Europe, Eastern European countries would understand that in the absence of new rules, the "new silk roads" could destroy their industries without lifting other distant populations out of poverty. Indeed, Chinese workers' wages have increased considerably, but Chinese industry now often uses labour located outside its borders and sometimes pays 40 euros ($50) for 200 hours a month. A wage increase for all workers working for export to major consumer markets could most often lead to an increase in the quality of manufacturing and materials used. This increase in value added, which would offset a decrease in export volumes, would also reduce consumerism. The means of communication and teaching deployed would include holding 100 to 200 conferences around the world in 2 to 3 years, providing real-time information on the progress of the project, increasing the number of forums in the international press and, more generally, using the most effective tools.

At a time when we are all concerned about the future of humanity and the loss of biodiversity, the "global minimum wage" could rebalance economic mechanisms and thus reduce the ravages of consumerism on the environment.

Consultant and entrepreneur, Francis Journot is the founder of the United States of Sub-Saharan Africa project and the Program for the Industrialization of Sub-Saharan Africa or Africa Atlantic Axis. He is also the initiator of the International Convention for a Global Minimum Wage and runs the website Collectivité Nationale

__________________________________________

There will never be a European

minimum wage

The "European minimum wage" advocated by French President Macron could be a hollow slogan

The "European minimum wage" advocated by French President Macron could be a hollow slogan

Le Figaro/Tribune by Francis Journot, published march 11, 2019 - While in his letter to Europeans, French President Emmanuel Macron advocated a "European minimum wage", Francis Journot believes that this proposal is inconceivable, and explains that it is only on a global scale that it is possible to imagine such a system.

In his manifesto "for a European renaissance" published on 4 March in the 28 EU countries, the French President Emmanuel Macron advocated "a European minimum wage, adapted to each country and discussed collectively each year". 22 countries already have a minimum wage ranging from 260 to 2,000 euros, which does not always guarantee decent living conditions, and conventional minima in countries without a minimum wage sometimes provide their workers with acceptable incomes. The heterogeneity of wages within the EU is therefore undeniable. Yes, but the slogan "European minimum wage" which appeared in the 1990s to announce a new social Europe and which is now being recycled by Emmanuel Macron, is not a project in its own right.

There will be no more European minimum wage than Asian or African minimum wage

In a globalised world, it is essential to understand these issues as a whole. Competition between low-cost countries is global. Also, few countries would tolerate economic interference in the name of wage homogenisation in the EU, which could not only reduce their competitiveness towards and with their European neighbours but also increase their wage cost differential with more distant countries (for example Ethiopia with sometimes monthly wages of 40 euros for nearly 200 hours worked). On Saturday, March 9, the new CDU president Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer (AKK), and perhaps future chancellor of a Germany that has many of its subcontractors in lower-cost eastern european countries, obviously expressed her disagreement.

On the other hand, at a time when everyone is concerned about the rise in inequality and the damage consumerism is causing to the environment, States could, within the framework of a global consensus, advocated in the concept of the "International Convention for a Global Minimum Wage", be more inclined to take a step towards a more virtuous model together.

After the First World War, the world minimum wage was one of the first projects of the ILO (International Labour Organisation), created in 1919 under the aegis of the Treaty of Versailles. Researchers most certainly quickly identified the most obvious ways at first glance, a global minimum wage based on a proportion of each country's median wage or income (50 or 60% often cited) and the living wage more or less close. These proposals have since been taken up by the defenders of the global minimum wage and by Emmanuel Macron today. But it can be assumed that ILO economists became aware of certain risks before the 1928 Convention. Indeed, the inclusion of a high or low median wage in the calculation of a local minimum wage does not guarantee that a State can then be able to cope in certain cases with an increase in the remuneration of its civil servants or that the inflation rate that could result from a generalisation of the minimum wage is contained and does not aggravate poverty situations. The danger of generating unrest and the bankruptcy of some states has certainly tempered the desire for social progress and encouraged caution. Also the Convention concerning the Creation of Minimum Wage-Fixing Machinery left it to the signatory States: "Each Member which ratifies this Convention shall be free to decide the nature and form of the minimum wage-fixing machinery, and the methods to be followed in its operation". 99 countries have ratified a convention that has not prevented inequality from growing. The global minimum wage has never seen the light of day.

The International Convention for a Global Minimum Wage project was first published in 2013 and now benefits from a global network of 3000 economists who know the proposals. Among these are many researchers and professors from prestigious American universities (Harvard, Stanford, Yale, MIT, Columbia, Berkeley and many others) but also several hundred economists working in international institutions such as the UN, WTO, IMF or ILO.  This project, which could be the only viable option for a global or European minimum wage, was sent on 19 February 2019 to the President of the European Commission Jean Claude Juncker. The proposal highlighted the difficulty of creating a European minimum wage outside a broader global minimum wage framework and suggested that the EU should take part in achieving this ambitious objective alongside international institutions. President Juncker has instructed the Commission's Director General for Employment and Social Affairs, Mr Joost Korte, to study the points raised. This measured concept with several levels of compatibility, offering a secure progressiveness and based on multiple parameters, would considerably reduce the risks of economic dysfunctions that could be feared when setting up a minimum wage. The theme of the European minimum wage advocated by Emmanuel Macron is certainly intended above all to attract voters concerned about social progress, but it is not certain that the choice of a minimum wage model that has proved impossible to implement for nearly a century is the right one.

This project, which could be the only viable option for a global or European minimum wage, was sent on 19 February 2019 to the President of the European Commission Jean Claude Juncker. The proposal highlighted the difficulty of creating a European minimum wage outside a broader global minimum wage framework and suggested that the EU should take part in achieving this ambitious objective alongside international institutions. President Juncker has instructed the Commission's Director General for Employment and Social Affairs, Mr Joost Korte, to study the points raised. This measured concept with several levels of compatibility, offering a secure progressiveness and based on multiple parameters, would considerably reduce the risks of economic dysfunctions that could be feared when setting up a minimum wage. The theme of the European minimum wage advocated by Emmanuel Macron is certainly intended above all to attract voters concerned about social progress, but it is not certain that the choice of a minimum wage model that has proved impossible to implement for nearly a century is the right one.

Consultant and entrepreneur, Francis Journot is the founder of the United States of Sub-Saharan Africa project and the Program for the Industrialization of Sub-Saharan Africa or Africa Atlantic Axis. He is also the initiator of the International Convention for a Global Minimum Wage and runs the website Collectivité Nationale

_____________________________

![]() After 40 years of failure, climate conferences

After 40 years of failure, climate conferences

must change their strategy!

Le Figaro/Tribune by Francis Journot, published january 31, 2019 - The first Climate COP was organised by the UN in Geneva in 1979. This year also saw the completion of the Tokyo Round under the GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and trade established in 1947). This decisive step in the first free trade treaty in history has led to an unprecedented acceleration in low-cost production and consumerism, but also in its perverse effects on the environment. We will not succeed in repairing this damage, but after the failure of the COP over the past 40 years, we must nevertheless try again to reconcile free trade, poverty reduction and environmental protection. ?

Defiance and green washing at COP 24

In December 2018, COP 24 was expected to finalize the 2015 Paris agreements, but judging by the absence of most of the 138 heads of state and government who were awaited and a disappointing result, we can only observe mistrust towards the climate strategy. But do the Paris agreements still make sense when they are ignored by the world's leading power and trampled underfoot by the second, obsessed with maintaining high growth and above all eager for industrial opportunities such as electric batteries, solar panels and wind turbines, for which it now holds monopolies? The other countries are not virtuous either. Germany, the largest economy in the EU, like many other countries, continues to invest in the coal sector, which accounts for 44% of global greenhouse gas emissions. This industry took the opportunity to do its green washing and the conference was sponsored by the Polish JSW, Europe's leading coal producer. The textile industry also wanted to improve its image because it ranks second among the most polluting industries behind the oil industry and has contributed, since the advent of fast fashion, to hundreds of ecological disasters. Every year, it releases 500 000 tonnes of microfibres into the oceans and still uses working conditions close to slavery with monthly wages sometimes below $60 or $120. Represented by 43 fashion groups, it has signed a charter to reduce its GHG emissions by 2050. However, the number of clothes and accessories manufactured has doubled in 15 years to reach 100 billion items per year and 10% of CO2 emissions. These figures could double again over the next 20 or 30 years according to the UN Environment: "If nothing changes, by 2050 the fashion industry will use up a quarter of the world's carbon budget".

In December 2018, COP 24 was expected to finalize the 2015 Paris agreements, but judging by the absence of most of the 138 heads of state and government who were awaited and a disappointing result, we can only observe mistrust towards the climate strategy. But do the Paris agreements still make sense when they are ignored by the world's leading power and trampled underfoot by the second, obsessed with maintaining high growth and above all eager for industrial opportunities such as electric batteries, solar panels and wind turbines, for which it now holds monopolies? The other countries are not virtuous either. Germany, the largest economy in the EU, like many other countries, continues to invest in the coal sector, which accounts for 44% of global greenhouse gas emissions. This industry took the opportunity to do its green washing and the conference was sponsored by the Polish JSW, Europe's leading coal producer. The textile industry also wanted to improve its image because it ranks second among the most polluting industries behind the oil industry and has contributed, since the advent of fast fashion, to hundreds of ecological disasters. Every year, it releases 500 000 tonnes of microfibres into the oceans and still uses working conditions close to slavery with monthly wages sometimes below $60 or $120. Represented by 43 fashion groups, it has signed a charter to reduce its GHG emissions by 2050. However, the number of clothes and accessories manufactured has doubled in 15 years to reach 100 billion items per year and 10% of CO2 emissions. These figures could double again over the next 20 or 30 years according to the UN Environment: "If nothing changes, by 2050 the fashion industry will use up a quarter of the world's carbon budget".

Why climate COP cannot succeed

The high number of climate septic countries and the economic influence of many of them, make these world summits irremediably doomed to failure. The very title of the Climate Conference, which presupposes anthropogenic origin, and the content of the Paris Agreements, which focus on global warming, are counterproductive. They neglect the divisions and relegate the issue of other environmental problems which could more easily federate, to the background. The IPCC's alarmist report did not reduce the camp of scepticism and UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres had to extend the last COP by 28 hours to obtain some non-binding commitments.

The divide will not disappear at the next COP and perhaps it is also necessary to break with an ideological and manichean vision that encourages a "North-South" opposition. The industry developed mainly from the beginning of the 20th century, but the damage caused to the environment has been mainly over the last four or five decades.

Also, some States consider that in a context of permanent economic war exacerbated by the globalization promoted by the GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and trade) and then the WTO, it is inconsistent to reproach them now for having followed this economic model which, 40 years ago, was also favoured by emerging or developing countries, even if some then benefited much more than others. At the end of the Tokyo Round in 1979, 102 signatory countries joined this choice of society that promoted growth and promised prosperity. The agreements then covered 300 billion dollars of trade instead of 40 billion in the previous round. Admittedly, everyone legitimately wanted development and poverty reduction for their country, but the risk of disastrous consequences, including the destruction of the environment, biodiversity and an increase in CO2 emissions, was already known. 60 other States joined them over the following decades. It is not surprising that the developed countries of the North, now judged by the Paris agreements, which are responsible for global warming and must therefore finance the energy transition of the countries of the South to the tune of 100 billion dollars per year from 2020, are not rushing to these global meetings or reluctant to write cheques, especially since a significant proportion of them do not feel responsible for the climate. It would be more consensual to rename the COP. A less ideological content that no longer confuses the various subjects, with new proposals and new insights into the less cleaved and concrete themes of demographic risk, environmental devastation and species extinction that no one can dispute, would make these conferences more credible and make it possible to combat GHG emissions more effectively.

Energy transition and electric cars: sustainable solutions or illusion?

It is regrettable that political parties and ecology NGOs have taken up the theme of global warming as their main focus and as a tool to influence domestic policies. This one now phagocytes the environmental debate. The Proposals that seem to be driven more by political ideology than by an interest in humanity often appear unrealistic. They are far from unanimous when they demand ever more energy taxes against consumers and businesses. The speech advocates the closure of fossil fuel power plants, but also in some countries of nuclear power plants that provide low-carbon electricity. But do we now have the necessary tools for a transition? Fossil fuels are polluting and nuclear waste difficult to store, but solar and wind energy can currently only provide complementary solutions in developed countries, given their intermittent nature.  However, the gradual adoption of this economic model, whose relevance has never been demonstrated, could lead to a significant increase in energy prices. It is also worth being cautious about the global ecological gain that could be achieved by apparently cleaner cars but whose electricity would in fact often come from coal, fuel oil or gas in neighboring countries or not. Emissions would decrease in metropolitan areas of countries with nuclear power plants, but pollution crosses borders. We can also fear the ecological risk of an anticipated replacement in a few years, of a large part of a fleet of nearly a billion cars in working order, with regard to the extraction of the necessary raw materials, the GHG emissions that would be generated by the production of billions of tons of materials, the management of car waste and new electric batteries that we do not yet know how to recycle and a ballet of container carriers that would also contribute to environmental pollution. The arrival on the market of tens of millions of additional cars per year, often subsequently exported (currently 4 to 5 million European vehicles are exported to Africa each year), would contribute to the suffocation of new cities.

However, the gradual adoption of this economic model, whose relevance has never been demonstrated, could lead to a significant increase in energy prices. It is also worth being cautious about the global ecological gain that could be achieved by apparently cleaner cars but whose electricity would in fact often come from coal, fuel oil or gas in neighboring countries or not. Emissions would decrease in metropolitan areas of countries with nuclear power plants, but pollution crosses borders. We can also fear the ecological risk of an anticipated replacement in a few years, of a large part of a fleet of nearly a billion cars in working order, with regard to the extraction of the necessary raw materials, the GHG emissions that would be generated by the production of billions of tons of materials, the management of car waste and new electric batteries that we do not yet know how to recycle and a ballet of container carriers that would also contribute to environmental pollution. The arrival on the market of tens of millions of additional cars per year, often subsequently exported (currently 4 to 5 million European vehicles are exported to Africa each year), would contribute to the suffocation of new cities.

When the pretext of ecology is used for taxation

The carbon tax, which is based on the polluter pays principle (PPP) that appeared in 1972, is proving inefficient. International groups often manage to avoid it and, above all, it increases the burden on local businesses and consumers in 21 countries, 17 of which are located in Europe, without reducing consumerism. In France, the "yellow vests" revolt began following a planned annual increase of €3.7 billion in fuel taxes presented to finance the energy transition. But of the 37.7 billion euros that were to be collected in 2019 under TICPE (domestic consumption tax on energy products), 7.2 billion euros or only 19.1% was allocated to the transition. It is not surprising that motorists who are already struggling to pay for food and vital energy rise up when the government wants to force them into debt for electric cars or new boilers.

The carbon tax, which is based on the polluter pays principle (PPP) that appeared in 1972, is proving inefficient. International groups often manage to avoid it and, above all, it increases the burden on local businesses and consumers in 21 countries, 17 of which are located in Europe, without reducing consumerism. In France, the "yellow vests" revolt began following a planned annual increase of €3.7 billion in fuel taxes presented to finance the energy transition. But of the 37.7 billion euros that were to be collected in 2019 under TICPE (domestic consumption tax on energy products), 7.2 billion euros or only 19.1% was allocated to the transition. It is not surprising that motorists who are already struggling to pay for food and vital energy rise up when the government wants to force them into debt for electric cars or new boilers.

Economic shortages and upheavals